|

|

|

The IAMLA Announces a Major Gift

from the

Cusumano Family

|

|

|

The Cusumano Family has joined the Museum's

elite cadre of donors known as the Founding Families.

In preparation for the Museum's opening, the IAMLA's Founding Family designation

was created to recognize individuals and families whose dedication, generosity,

and achievements make them ripe for distinction. |

|

|

|

The Cusumano Family Story

|

|

|

The commune, or

municipality, of Menfi, Sicily erupted in celebration as the statue of

its patron saint, San Antonio, mounted on a massive wooden pedestal,

passed through the streets. The village musicians, playing the

ciarabedda (bagpipes),

friscalettu (flute),

marranzanu (jaw harp), and

tammurinu (tambourine), provided the distinctively Sicilian

serenade for the march, in which hundreds of the townspeople

participated. For the faithful, the feast day was an occasion to offer

gratitude for the blessings received over the past year and request the

saint’s benedictions for the year to come. With a candle in her hand,

Anna Scirica Cusumano observed the spectacle solemnly from the doorway

of her home, knowing, perhaps, it would be her last in the town.

|

|

|

Early 20th century view of Menfi, Sicily, courtesy of Archivo Menfi.

|

|

|

She located her

elder sons, Salvatore, age eleven, and Michele, age nine, who were

waiting eagerly for the firecrackers to be lit. In the adjacent

courtyard, where the prickly pear orchard permanently stained portions

of the floor a murky, purple-red, Anna’s daughters, sixteen-year-old

Filomena and thirteen-year-old Leonarda, stood with the women of the

Cusumano and Scirica families in front of an enormous, steaming,

terracotta pot of

cacio e fave, or fava beans and sheep’s milk cheese, the traditional dish prepared in San Antonio’s honor.

|

|

|

After returning to

the upstairs room where her tightly swaddled infant son, Calogero, slept

soundly, Anna sat next to the family’s wooden trunk and continued her

work. “Take only what you and the girls can carry in two sacks each,”

Anna’s brother had instructed her. In a few months, Anna, Calogero,

Filomena, and Leonarda would be leaving Sicily, and Anna faced the

unpleasant task of selecting which of the family’s few material

possessions would be taken with them and, conversely, which belongings

would be left behind. An exceptionally talented seamstress, Anna, like

many women of her era, had begun to compile items for her daughters’

corredo, or linen trousseau, almost immediately following their

birth. The corredo comprised an important part of her daughters’

dowries, a custom deeply rooted in Italian society since ancient times.

Filomena and Leonarda’s dowries were an indicator of the family’s social

standing; moreover, they were regarded as the material foundation for

future generations.

|

|

|

Above: Nuptial sheet embroidered with the words “buon riposo” (rest well).

From the collection of the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles.

|

|

|

At

the very top of the chest was one of Anna’s proudest creations, a

nuptial sheet that she had embroidered with an intricate design of

cherubs and flowers. She smoothed her hand across the crisp linen

fabric. Anna could not bear to part with it; the sheet would come to

America. As she bent down to retrieve the next item from the trunk, Anna

caught a glimpse of the enormous, red-orange Sicilian sun, which, as it

sank into the horizon, bathed the vineyards and wheat fields in a

pink-scarlet light.

Right: Contemporary view of Menfi, Sicily, at sunset. Image courtesy of Khirat.

|

|

|

|

|

It was August 12,

1911. The scent of lavender, rosemary, and citrus perfumed the air, and

gazing into the distance, where Menfi’s parched, rolling hills met the

impossibly blue water, Anna recalled the months leading up to her own

wedding, nearly two decades earlier.

|

|

|

Above: Map of western Sicily. Menfi's location is indicated by the red pin.

Anna Scirica was seventeen years old when she first learned of

Giuseppe Cusumano’s interest in marrying her. The Scirica and Cusumano

families belonged to the same intricate kinship network in Menfi,

situated in the southwestern province of Agrigento, between Sciacca and

Castelvetrano. Present-day Menfi is said to be located on the site of

Inycon, an ancient city founded by one of the earliest peoples of

Sicily, the Sicani, whose presence on the island can be traced to 1600

BCE and predates the arrival of the Greeks and Phoenicians. Greek

writers, including Herodotus and Ovid, described Menfi’s “fine wines”

and its legendary king, Kokalos, who appears in the myth of

Daedalus and Icarus. |

|

|

|

During medieval times, the region was known as

Burgiomilluso, which some scholars contend translates to

“pleasure castle” in Arabic. Local culinary specialties, such as

couscous, marzipan, and rabbit cooked in chocolate, provide lingering

evidence of Sicily’s period of Muslim occupation. In the early 1500s,

when Spain ruled the island, the district was renamed

Burgetto. It was then that Charles V granted Duke Giovanni

D’Aragona Tagliavia permission to establish an agricultural colony,

originally known as

Menfrici, in the area surrounding the ancient castle of Burgiomilluso.

Right: Drawing of King Frederick II of Swabia, builder of the Castle of Burgiomilluso, from the Vatican Library.

|

|

|

|

|

Above: Receipt for rent paid by the Cusumano family to the estate of Prince Pignatelli.

|

|

|

Since local endogamy

was customary, Anna and Giuseppe’s union had, in all likelihood, been

decided years before Giuseppe’s father, Salvatore Cusumano, visited

Anna’s father, Michele Scirica, to declare his son’s intentions. While

both families were considered members of the peasant class, a plethora

of social distinctions existed within and among the peasantry. A

sheepherder, for instance, was superior to a goatherd; farmers ranked

higher than fishermen, and all stood above the

bracciante, or agricultural laborer. Terms such as

propietari (peasant proprietor),

burgisi (land-owning

peasants), and

viddani (peasants who did not own land), indicated one’s

position in the hierarchy and determined the level of respect the

individual received. Salvatore Cusumano leased acreage from the estate

of Prince Federico Aragona Pignatelli, a descendant of Menfi’s founder,

Duke Giovanni D’Aragona Tagliavia. Anna assumed that her father would

reject Giuseppe’s marriage proposal, and when he did not, in a desperate

attempt to exercise agency over her destiny, she protested to her

mother.

“Non è della mia condizione!” ("He is not of my class!")

|

|

|

Anna and Giuseppe were married in January of 1895 and lived in a

two-room home above the shed-like compartment where their animals were

housed. The

following year, Anna gave birth to Filomena; the couple’s next surviving child, Leonarda, arrived two years later.

Hoping, perhaps, to cement their association with an echelon

superior to that of agricultural laborers, Anna began teaching her

daughters how to sew shortly after they learned to walk. By honing their

skills as seamstresses and becoming competent in the production of

other

handicrafts, Filomena and Leonarda would contribute to the family’s

social and economic wellbeing while developing qualities that would make

them attractive to future suitors.

Left: Anna Scirica’s document dotale, or dowry document.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sicilian peasant women, circa 1900.

By 1900, large

landowners owned 90% of Southern Italy’s land, and to promote industry

in northern Italy, the Italian government imposed heavy taxes on the

southern peasantry. Each morning, Giuseppe awoke before dawn and

traveled on foot to a tiny, overworked plot of land on the outskirts of

town. While wages remained dismally low in the south – $.50 for twelve

hours of labor – the cost of living and basic foodstuffs, such as sugar,

which cost $.19 a pound, skyrocketed. The owners of the large estates

monopolized water rights, privatized roads, and charged exorbitant fees

for the usage of both. The Cusumano family paid taxes on the animals

they owned, as well as on the crops they cultivated. As the southern

Italian economy collapsed, Anna gave birth to sons Salvatore, born in

1900, and Michele, in 1902. Fleeing poverty, disease, natural disasters,

and political and social inequities, by 1910, one-third of Menfi’s

population had immigrated to the United States. Many other Menfitani

settled in South America, specifically in Argentina, where the economy,

driven by the export of agricultural products, was growing at such an

impressive rate that it was expected to become the “United States” of

South America.

|

|

|

|

One September evening in 1909, following the family’s typical dinner fare of

minestre, a thick vegetable soup, and hard, crusty bread, Anna and Giuseppe

exchanged words, which rapidly became heated. “Ma c’è lavoro lí!”

(But there’s work there!) Giuseppe insisted, referring to Fuentes,

Argentina, to which several members of his family had recently

relocated. Enticed by their glowing reports of abundant employment, a

temperate climate, and affordable land, Giuseppe was convinced that

Argentina offered a future that was impossible to achieve in Menfi.

“They will make you a slave!” retorted Anna, citing the numerous

incidents of Italian agricultural workers being forced into servitude in

Brazil, which led the Italian government to ban

immigration to the country.

Right: Informational pamphlet produced by the Italian government, for citizens emigrating to Brazil.

|

|

|

|

|

For

Anna, who had never traveled beyond the confines of Menfi, much less

seen a world map, Argentina and Brazil could just as easily have been

neighboring villages. Giuseppe ignored Anna’s remark. “We can buy land

there!” he continued. Her husband’s words provoked a mental image of

Filomena and Leonarda, bent over, clad in handkerchiefs, working in the

fields of Argentina. “No!” she proclaimed emphatically before turning

and walking away.

Anna’s stubbornness was nothing new to Giuseppe; a demure woman she was not. When he bid farewell to his wife and children weeks later, Giuseppe believed it would only be a matter of time before the family was reunited. He would establish himself in Fuentes, and Anna would come to her senses. Weeks after her husband’s departure, Anna discovered she was pregnant with their fifth child. With the assistance of a mid-wife, Anna gave birth to Calogero in the family’s one-room home on Via Soccorso. She joined the ranks of the town’s many “white widows,” the name used to describe women who fended for themselves and their children after their husbands left in search of work abroad.

|

|

|

|

Although four years her junior, Anna’s brother, whose name was also Giuseppe, was deeply protective of his sister and the

children. Shortly before his brother-in-law’s departure, Giuseppe

Scirica had immigrated to America and settled in the Bushwick section of

Brooklyn, New York, alongside scores of fellow Menfitani. When he

learned of his sister’s plight, Giuseppe returned to their village, and,

after placing her sons Salvatore and Michele in the custody of family

members, on March 14, 1912, Anna, along with Filomena, Leonarda, and

baby Calogero,

boarded the

SS Oceania with Giuseppe at the port of Palermo. Anna and the girls planned to find work in New York’s

burgeoning garment industry and pay for Salvatore and Michele’s passage. Anna had another reason for insisting that

her daughters make the transatlantic journey prior to their

brothers, however. If left in Sicily without a guardian, they would

marry out of necessity, Anna feared, further dividing an already fractured family.

Left: Giuseppe Scirica, shortly before his departure to America.

|

|

|

|

|

The SS Oceania, the ship that Giuseppe and Anna Scirica and children Calogero, Filomena and Leonarda Cusumano took to the United States. |

|

|

|

1912 ship manifest for Giuseppe and

Anna Scirica, Calogero, Filomena, and Leonarda

Cusumano

|

|

|

Anna and her daughters

secured employment in a sweatshop, where they made $3.50 a week,

working ten-hour days, six days a week, and frequently took home

piecework to earn extra money. One year earlier, the Triangle Shirtwaist

Factory Fire, the deadliest industrial disaster in New York City

history, claimed the lives of 146 people, largely Italian and Jewish

immigrant women and girls, who perished in the inferno or jumped several

stories to their deaths after being trapped in the building. To prevent

workers from taking unauthorized breaks, the factory owners had chained

the exit doors shut. While the fire galvanized reform efforts and

produced legislation requiring improved workplace safety standards and

working conditions, change was slow to come.

Above: Front page of the New York Herald depicting the carnage of the

Triangle Factory Fire.

|

|

|

|

Anna’s, Filomena’s, and Leonarda’s limited English proficiency and status as immigrant women relegated them to the

most dangerous and lowest paying jobs. But in less than a year’s

time, they had managed to save enough to pay for Salvatore and Michele’s

passage. The family, minus its patriarch, was reunited at last.

From left Salvatore and Michael Cusumano, Anna Scirica (seated) and young Calogero “Charles” Cusumano,

approximately a decade after their arrival in America.

|

|

|

|

|

Anna and the children followed Giuseppe, whom they referred to affectionately as

Uzzu Bep, which means

Uncle Joe in their Sicilian dialect, to Hartford, Connecticut.

Uncle Joe had become a successful truck farmer and beloved fixture at

the Charles Street Market, where he sold the produce he grew from a

horse-drawn cart. Although Italians were the poorest paid workers in

Hartford, earning substantially less than their Irish and German

immigrant counterparts, the city’s employment and entrepreneurial

opportunities—in

construction, railroads, factories, and the service and retail

sectors—attracted many immigrants to the area. By 1910, 14 percent of

Hartford’s population was Italian, two-thirds of whom lived in the Front

Street neighborhood, before urban renewal forced Little Italy’s

relocation to Franklin Avenue, on the city’s south end.

Below left: Produce cart at the

Charles Street Market in Hartford’s little Italy, circa 1920. Courtesy

of the Connecticut Historical Society. Below right: Early 1900's view of Front Street in Hartford. Courtesy of the Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library.

|

|

|

The Cusumano-Scirica

family, like other immigrant families of the era, was both a social and

economic unit to which all members contributed, working collectively to

ensure its survival. Raising five children as a single parent in a

country that remained largely alien to her, Anna fought to uphold the

belief system and cultural practices of the Old World while filtering

the often conflicting values of their adopted homeland. Above all, she

loved and protected her children with the instincts of a lioness. The

bond between Anna and her youngest son, Calogero, who Americanized his

name to Charles, was particularly strong. By age six, Charles worked as a

shoeshine boy and faithfully remitted his earnings to the family

coffer. His gentle, chestnut brown eyes exuded a wisdom that far

surpassed his chronological age. After completing the sixth grade,

Charles left school to assume a larger role in the family’s support.

|

|

|

Left: Calogero “Charles” Cusumano, age 10. Right: Siblings Charles, Michael, and

Filomena Cusumano with their mother, Anna Scirica.

|

|

|

Soon, the United States descended into the darkest hours of the Great

Depression, and in search of employment, Charles traveled between

Connecticut and New York, accepting any honest work he could obtain. He

walked miles and hours at a time distributing flyers; he farmed pigs,

laid cement and did carpentry. Every so often, Giuseppe sent the family

letters from Argentina.

Dearest ones,

Much time has passed since I have received news from you. We are

about to enter the winter season here. Money is scarce and the crops are

poor….

At age 25, Charles saw his father for the

first time in a photograph.

Giuseppe Cusumano,

photographed in Argentina,

circa 1930.

|

|

|

|

|

In 1935, Charles secured a position at a Brooklyn butcher shop. The proprietor,

Mr. Rossi, had met the young Charles Cusumano nearly twenty years earlier, when, not

yet four feet tall, Charles had offered to clean the sidewalks in

front of the shop on his way to school in the morning. Rain or shine,

Charles faithfully reported to work, and Mr. Rossi never forgot the

young man’s work ethic. Charles vaguely resembled the heartthrob Rudolph

Valentino. Slim and muscular, his dark hair, combed neatly back,

accentuated his high cheekbones, chiseled jaw, and bow-shaped mouth.

Charles seldom took notice of how young women, and a few who were not so

young, stammered nervously when he took their orders behind the butcher

counter. One afternoon, after being cajoled by her sister,

twenty-one-year-old Anita DePaola entered the butcher shop and waited

patiently in line, hoping that it would be Charles who would assist her.

|

|

|

Left: Charles Cusumano dancing with a friend, late 1920’s. Right: Anita De Paola in high school.

|

|

|

Anita De Paola was

born in New York City shortly after her parents, Caterina Magnetti and

Pasquale DePaola, immigrated to the United States. The family, which

would soon include two additional children, Joseph and Vera, lived in

the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, not far from Central

Park. The DePaola children did not learn English until they entered

elementary school, and they cherished the opportunities offered to them

through the nation’s public school system. Anita and her siblings

represent the transitional generation of Italian Americans; while they

spoke exclusively Italian at home, they were among the nation’s proudest

citizens. During World War II, Joseph DePaola enlisted in the United

States Army. Deployed to the western front, Joe, a tank driver, served

in the Battle of the Bulge, the surprise blitzkrieg attack by Nazi

forces on Allied troops in December of 1944. The United States incurred a

higher number of casualties in the Battle of the Bulge than in any

other operation during the war. Shortly before his 50th birthday,

Anita’s father died unexpectedly, at which point the DePaola siblings

were required to assume a greater role in supporting the household.

Anita and Vera became clerks at a department store; Joe painted houses.

|

|

|

Left: Wedding photo of Caterina Magnetti and Pasquale DePaola.

Right: Joseph De Paola, in his army uniform, 1942.

|

|

|

Anita and Charles began to date and, after a brief courtship, were

married in 1938. The following year, the couple welcomed their first

child, Ann. In 1941, a son was born, named Charles Pasquale after his

father and maternal grandfather. The family, including Charles’ mother,

Anna, lived in a humble, three-story walk-up in Bushwick. For Charles,

parenthood filled the unassuageable lifetime void of his father’s

absence; his family existed at the very center of his life. In search of

better opportunities and the possibility of

homeownership, relocated the family to East Hartford, Connecticut,

where he opened a butcher shop. Shortly thereafter, two more children

were born, Roger and Joseph.

Wedding photo of Anita DePaola, seated left,

and Charles Cusumano, (standing above her).

|

|

|

|

|

Left to right: Charles Pasquale, Ann, and Roger Cusumano

|

|

|

Oh, I'm packin' my grip and I'm leavin' today

'Cause I'm takin' a trip, California way

I'm gonna settle down and never more roam

And make the San Fernando Valley my home.

Right: Sheet music for Bing Crosby’s

San Fernando Valley

|

|

|

|

|

World War II had ended, Bing Crosby’s

San Fernando Valley was among the top hits on the

Billboard chart, and Charles pursued his lifelong dream of visiting

California. During his two-week stay, he fell in love with the region’s

climate, lack of congestion, and idyllic communities, where many young

families like his pursued and appeared to achieve the American Dream.

After returning to Connecticut and sharing the news with

his family, preparations began for their impending move. Charles

purchased a 1948 Packard Super 8, and later that year, the Cusumano

family packed their possessions tightly in the trunk and drove to

California. |

|

|

While her youngest son, Joe, slept on her lap, Anita helped Ann and Roger pass time playing

I

Spy, and twenty questions. In the back seat, next to Grandma

Anna, seven-year-old Charles Pasquale, or “Chuck,” rested his chin on

the passenger door, his forehead pressed against the window, and

observed the scenery as the family traveled west along Route 66: the

gray and desolate coal mining towns of Pennsylvania; the rich greenery

of the Ozarks; and the vibrant, multihued badlands of Arizona’s Painted

Desert.

After five days on the road, Chuck began to crave his mother’s

exquisite cooking, namely Anita’s rich marinara sauce served over

mostaccioli with a generous grating of

Pecorino Romano cheese.

Charles “Chuck” Cusumano, age six.

|

|

|

|

|

That evening, as the family sat in a roadside diner, Chuck was delighted to discover that the establishment’s menu included

spaghetti with tomato sauce. “They have it!” Chuck informed his

parents triumphantly. “You are not going to like it,” his father

warned, shaking his head. “It will not be like what we eat at home,”

Anita cautioned. But Chuck was salivating; he needed pasta! When the

food arrived, Chuck looked at his plate in disbelief. The noodles were

pasty, white, and stuck together in clumps. On top was a smattering of

watery, orange sauce and a sprinkle of a soft, unidentifiable cheese. It

tasted horrible.

Right: The Cusumano family shortly before relocating to California.

|

|

|

|

|

|

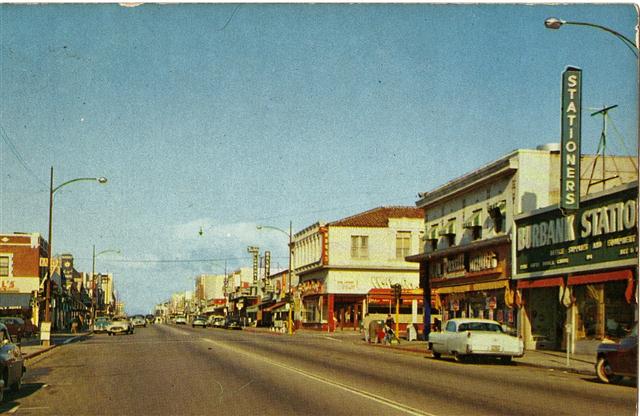

1950's view of San Fernando Road in Burbank, California

Upon their arrival in

Southern California, the Cusumanos stayed briefly in an Inglewood motel

while Charles found a suitable home. He considered a number of

neighborhoods before selecting Burbank, a city in Los Angeles County

located twelve miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles. In the late

1940's, Burbank was home to a population of approximately 78,000; many

of its residents were employed in the aircraft industry or at the area’s

motion picture studios. For Charles and Anita, the 1,000 square foot,

three-bedroom house on a quiet, tree-lined street represented a little

piece of paradise, and they promptly began making improvements to the

property. Although the four Cusumano children shared a bedroom no larger

than 9’ x 10’, and the seven-member household made use of a single

bathroom, the tightly knit family never felt cramped. The Cusumano home

became the focal point for family, friends, and neighbors who gathered

at the house frequently for card games, dinners, and holidays.

|

|

|

|

|

Charles Cusumano reads to daughter, Ann, while Anita tends to

Chuck.

As parents, Charles and Anita understood the importance of

integrating their children into what was considered conventional

American culture in the hope that one day, Ann, Chuck, Roger, and Joe

might access the benefits of becoming middle class. At home, they spoke

exclusively English with their children. In the evenings, after returning from his job at Ralph’s supermarket, where he worked as a

butcher, Charles sat in the family room he built, the children nestled

at his side, reading them stories and sharing the wonders of distant

places via

National

Geographic. To an extent that surpassed most of his

contemporaries, Charles played an active role in his children’s lives. A

stern disciplinarian, he was determined to raise his

children to be well rounded and made all the sacrifices necessary to

ensure that their formative years were filled with a myriad of

activities, from dance and horseback riding to boy scouts, archery,

music, and boxing lessons. |

|

|

|

Charles and his children at Pickw

ick Stables in Burbank.

Anita played an

equally important role. Broad-minded and energetic, Anita was the

driving force behind familial cohesion. The emphasis she placed on food

served as the foundation of her children’s, and later her

grandchildren’s, understanding of their Italian heritage. Prepared

without written recipes or measuring cups, Anita’s meals continue to

occupy a legendary status in the

Cusumano family. To Anita, food was not merely nourishment; it was life, love, nurture, and pride.

|

|

|

|

Above: The Cusumano family at home in Burbank and Anita’s recipe for white clam sauce.

The family gathered

religiously for dinner every night, and before going to work each

morning, Anita made her children a complete breakfast and packed them a

well-balanced lunch. During the summer months, three generations of the

Cusumano family piled into the car and headed west to Santa Monica

Beach. The children disappeared in the water for hours before returning

to the shore, where Anita was waiting with a brown bag full of

sandwiches she had made that morning. With saltwater dripping from their

hair, their fingers shriveled like prunes, Roger and Chuck tore into

their sandwiches hungrily. With each bite, they received a proud

reminder of their family’s origins. While the other kids ate peanut

butter and jelly on white, airy bread, the Cusumano siblings

feasted on

prosciutto sandwiches made with freshly baked Italian rolls. When the weather was cold or a family member was ill, an enormous pot of

stracciatella—a chicken broth-based soup into which beaten eggs

and Parmesan cheese have been stirred—could be found gently simmering

on her stove. The intoxicating scent of Anita’s

eggplant parmigiana and

agnello al forno, or baked lamb, floated tantalizingly across

Kenwood Street, leading many neighbors to wish that they were dining

with the Cusumanos that evening. At Christmas, Anita enlisted the

children to help decorate, and the home buzzed with excitement. An

enormous platter of

struffoli, or honey-drenched fritters, adorned the dining room table, alongside a dozen other delicacies, such as tender

braciole (stuffed flank steak); homemade ravioli; and

rapini, a vegetable similar to broccoli, sautéed in garlic,

olive oil, and lemon. Shortly before her death in 1998, Anita

transcribed her recipes, along with the memories connected to them, into

a journal. That journal has since been replicated and bound, with a

copy given to each of Anita’s children, grandchildren, and

great-grandchildren. It is among their most treasured possessions.

|

|

|

Anna Scirica with her grandchildren.

While Grandma Anna’s limited English made communication challenging,

she loved her grandchildren with the same fervor as her children. One

day, Chuck and the neighborhood kids decided to stage a wrestling match

on the Cusumano front lawn. Unbeknownst to Chuck, Grandma Anna watched

intently from the kitchen window. At first, Chuck bested his opponent in

a playful headlock and double-leg takedown. He did not notice the

commotion that erupted in the kitchen when the neighbor boy pinned him

down on the grass, however. Sensing that her grandson was in danger,

Grandma Anna, armed with a broom and dressed in widow’s black, came

running out of the house and began swatting Chuck’s

opponent while hurling a collection of colorful Sicilian curses at the perceived assailant. |

|

|

|

From an early age, Charles imparted to his children the same values

that continue to guide them today: hard work, discipline, frugality, and

above all, the importance of family. The family did everything

together. The Cusumanos arrived at Ann’s monthly tap dance recitals

early to reserve choice seats in the front row of the auditorium. When

Roger received the Cub Scout Outdoor Activity Award, the entire family

watched proudly. Before the Cusumano children entered elementary school,

each child was assigned a list of responsibilities within the home,

including mowing the lawn, tending to the front garden, and washing and

waxing the kitchen floor. Constantly in search of ways to earn money,

Chuck, Roger, and Joe collected empty bottles, which they would return

for the deposit.

Ann Cusumano (left) at a dance

recital.

|

|

|

|

|

Young Charles Cusumano mows the family’s front lawn.

|

|

|

|

Roger often knocked on

neighbors’ doors, offering to cut their grass. The brothers also raised

rabbits in the back yard, which Charles would butcher. The boys then

sold the meat to neighbors and the pelts to a furrier. By age nine,

Chuck had secured a paper route with the

Herald Examiner. On his first day, after reporting to work at 6

a.m., he received ten copies of the paper to sell. At that time, each

Sunday paper was approximately three inches thick and quite heavy. As he

set off toward Hollywood Way, Chuck struggled to carry the load until

it became unbearable. He would not accept defeat, however. Chuck ran

home and burst into the bedroom where Roger and his siblings slept.

“Wake up!” he said, shaking Roger. “I need you to help me!” After a

small amount of coaxing, Roger joined his brother on the route. Chuck

Roger, and Joe proved themselves successful salesmen, and the

Examiner rewarded the brothers with a wagon. Charles promptly

extended the wagon’s sides, thereby allowing his sons to transport large

quantities of newspapers, and within three months, the trio had sold

more papers than any other paperboys in the area, prompting the

Examiner’s rival, the

Los Angeles Times, to approach the brothers and offer them a route.

|

|

|

On payday, the Cusumano children dutifully relinquished their

earnings to their father. Charles gave each child a weekly allowance of $

.25 and deposited the remainder into the children’s savings accounts.

Using their savings, the Cusumano children purchased their own clothing

and financed their leisure activities and major purchases. For Chuck and

Roger, this provided their earliest lesson in the value of labor and

the allocation of resources.

Roger (left) and Chuck (right) Cusumano

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The Cusumano brothers (l-r) Chuck, Roger, and Joe, in high school.

Right: Charles Cusumano walks daughter Ann down the aisle on her wedding day.

|

|

|

During Roger’s

freshman year and Chuck’s sophomore year in high school, Charles

discovered a black mole on his second toe, which was promptly diagnosed

as a malignant melanoma. After a series of operations and aggressive

treatment, doctors informed the family that Charles’ condition was

terminal. The patriarch of the Cusumano family walked his daughter down

the aisle on her wedding day in November of 1957 before succumbing to

his illness seven months later; he was only 48 years old. Loved by all,

hundreds of community members attended the funeral. Although devastated

by her husband’s death, Anita remained strong for her children. She

commuted by bus from Burbank to Hollywood, where she worked long hours

as a cashier at Woolworth and eventually became the store’s bookkeeper.

Her dinner table remained the place where the family gathered to chat

about their days, celebrate successes, and console one another during

times of need.

|

|

|

|

Evelyn and Roger Cusumano with their children Anthony and Julie.

While Anita had hoped that her children would attend college,

following their father’s passing, Chuck, Roger, and Joe felt a greater

urgency to work and contribute to the family’s support. After graduating

from John Burroughs High School in Burbank, Joe served in United States

military and worked as a film processor for Hollywood studios. Chuck

became a meter reader for the gas company; he discovered, however, that

ascending the company’s professional ladder required a college degree.

Roger, meanwhile, hoped to become a plumber, but because most jobs in

the trade were union, Roger faced tremendous obstacles. He secured a job

at a sheet metal firm; within two years, he had become a journeyman

and, shortly thereafter, the metal shop’s manager. One evening, while

bowling with Chuck, Roger noticed a golden-haired beauty with gentle,

olive green eyes in the adjoining lane. He learned that her name was

Evelyn. Seeking the curative qualities of Southern California’s

climate, in 1954, Evelyn’s family had emigrated to the region from

Paxton, Illinois, where they had been tenant farmers. In 1967, Roger and

Evelyn were married and were soon blessed with two children, Julie and

Anthony.

|

|

|

|

Dianna and Chuck Cusumano with their first child, Michael.

At age 21, Chuck

married Texas-born Dianna Hansen; the couple welcomed their first child,

Michael, in 1962. Another son, Charles, or Charlie, soon arrived. To

provide for his rapidly growing family, which, in a matter of nine

years, included three more children, Christina, Daniel, and Matthew,

Chuck obtained a real estate license in 1964. He awoke early each

morning, completed his work at the gas company in four hours instead of

the eight allotted, and, in the afternoons, sold real estate. Chuck was

an incredible salesman who averaged over 100 transactions annually.

Moreover, he recognized the investment vehicle that real estate provided

and became intent on becoming an investor and developer.

|

|

|

|

In 1965, Chuck learned

of a building in Burbank that the owner desperately needed to sell. The

nine-unit apartment complex was heavily encumbered in debt with

considerable deferred maintenance. Using the equity in Chuck’s home and

capital that Roger provided, the brothers purchased the property. To

break even, they performed all the building’s repairs and maintenance.

Chuck and Roger soon began purchasing additional properties and

mortgages and, following their father’s teachings, reinvested the

profits. In 1968, Chuck became a real estate broker and officially

parted ways with the gas company. He acquired Gem Realty, the firm where

he had worked as an agent. The brothers bought land in Burbank,

Glendale, and elsewhere in Southern California, on which they built

housing, commercial, and industrial developments, and Roger left his job

in construction to dedicate his attention to the family’s ever-growing

real estate portfolio.

|

|

|

L-R: Charlie, Michael, Danny, Tina, Dianna, Chuck, and Matt Cusumano

In Chuck’s effort to impart to his children the work ethic that his

father had instilled in him, Chuck brought his sons to work. From age

seven onward, in the afternoons, weekends, and throughout the summer,

Michael, Charlie, and later, Daniel and Matthew, could be seen at the

family’s properties, mowing lawns, mopping floors, and making repairs.

While attending John Burroughs High School in Burbank, Michael, Charlie,

and Danny earned high marks and particularly excelled at football. The

three brothers earned the distinction “All-League” in football and

played on championship teams. In keeping with the values his parents

instilled in him, Chuck taught his children the importance of family;

they gathered every evening at the dinner table. Chuck took his children

skiing, fishing, camping, and hunting, and he and the children

exercised together in the morning.

|

|

|

|

Charlie (second from left), Chuck, Roger and Michael Cusumano (far right) at the ribbon cutting for Cusumano Plaza in 1990.

In the early 1980's, the City of Burbank acquired a 2.1-acre parcel of land on First Street and Olive Avenue, which it subsequently earmarked for re-development. The Cusumano Real Estate Group submitted a proposal to construct a 65,000 square foot office on the site, not far from Burbank’s fledgling “restaurant row.” |

|

|

|

While the City of Burbank

was initially resistant to the idea of office space, preferring an

occupant of the restaurant or entertainment genre, Chuck personally

financed the project’s construction and delivered the highly sought

after tenant, Bobby McGee’s. Founded by Bob Sikora, Bobby McGee’s was a

nightclub restaurant with an eclectically themed décor and costumed

waiters. Designed to be a “symphony for the senses,” with dozens of

locations worldwide, the serendipitous nightclub chain became among the

most successful in the world. Its Burbank location was a destination,

drawing patrons from across the region.

Chuck Cusumano, second from left, on the cover of Burbank Business Today magazine, which praised the opening of Bobby McGee’s.

|

|

|

|

|

L-R: Danny, Charlie, Chuck, Matt and Michael Cusumano

In 1984, at the age of

21, Michael earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University

of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), becoming the first member of the

Cusumano family to graduate from college. He continued his studies at

Pepperdine University, where he graduated first in his class with a

master’s degree in business administration. Between 1984 and 2015,

Michael supervised the development or acquisition of over 100 major real

estate projects. During his college years, Charlie, who studied

business administration at the University of

Southern California (USC), assumed an integral role in the company,

reporting to construction sites in the early morning before class and

returning to the office in the afternoon.

|

|

|

|

L-R: James and Sergeant Charles

Felice Cusumano, James Isom, Diana Cusumano Isom, Marshall Hall,

Samantha Cusumano Hall, Bettina, Charlie, and Chuck Cusumano

Under Michael and Charlie’s direction, the Cusumano Group pursued a relentless

program of growth, undertaking the development of dozens of

properties in the region. Charlie and Michael established construction,

development, and property management divisions. Today, Charlie oversees

the Cusumano Group’s extensive holdings in commercial real estate, which

includes office buildings, retail centers, restaurants, and other

facilities throughout Southern California. After earning a degree in

international relations from Brigham Young University, Danny joined the

family business. Matt, a graduate of the University of Utah, also

entered the real estate field. Tina is the dedicated mother of three

children.

|

|

|

|

L-R: Felice, Justin,

Danny, Chuck, Roger, Charlie, and Michael Cusumano at the December 2015

groundbreaking of Talaria at Burbank. |

|

|

|

Over the past five

decades, the Cusumano name has become synonymous with quality real

estate development, property management, leasing, and construction. As

the Cusumano Real Estate Group entered the 21st century, it continued to

expand its portfolio, acquiring and developing many significant

properties. From 2010 to 2015, the family was among the most prolific

buyers of real estate in the region, despite the challenges that the

national economy was facing. Today, the family is one of the largest

privately held property owners in Southern California, and three

generations of the Cusumano family are involved in the business. While

their contributions can be detected

throughout the region, the Cusumano Real Estate Group’s greatest

impact has been on the revitalization and economic growth of Burbank.

One of the projects that best exemplifies the manner in which the

company has changed the face of the area is the

Talaria at Burbank mixed-use project.

|

|

|

Rendering of Talaria at Burbank

First envisioned in 2007, the project, which encompasses two city

blocks, required the assemblage of approximately 25 separate parcels of

land, as well as

extensive public hearings, before it was finally approved in late

2014. The development features a 43,000 square-foot Whole Foods Market

and 241 luxury apartments. At 425,000 square feet, Talaria at Burbank

comprises the largest mixed-use residential property ever constructed in

the City of Burbank. It is also the city’s first LEED-certified

mixed-use property. By providing first-class and innovative facilities

for quality, compatible, long-term tenants, including Disney,

JP Morgan Chase and Co., Wells Fargo, and Amgen, the company has

generated tens of millions of dollars in public revenue, provided

housing for thousands of families, and created an equal number of local

jobs.

|

|

|

|

|

Premiere on First, the high rise hotel, office, and apartment complex, currently in

planning for 2016.

The company’s holistic approach to development, ownership, and management

exceeds commonly prescribed industry norms and is widely recognized

for enhancing the community’s quality of life. A few of the Cusumano

Real Estate Group’s other flagship projects are Cusumano Plaza, a 65,000

square-foot office complex with a 7,000 square-foot restaurant and a

145,000 square foot parking structure that was recognized by the Burbank

Civic Pride Committee as the best development in the city. The Cusumano

Group’s 163-unit Olive Court Senior Apartments provides housing to

low-income seniors in conjunction with unheard of on-site services,

amenities, and programs, such as adult education classes, monthly

communal dinners, and yoga, and is regarded as one of the finest senior

housing facilities in the region. One of the company’s current focuses

is implementing environmentally responsible and sustainable practices in

its development projects, some of which are LEED-certified.

|

|

|

|

|

On her 80th birthday,

Anita Cusumano, sons Chuck and Joe (center), grandson Michael (right),

and great-grandson Tanner celebrate a generous gift made by the family

in Anita’s name to

Providence St. Joseph Medical Center.

Following the example set by Cusumano matriarch Anita Cusumano, who, for

over twenty years, volunteered daily at Providence St. Joseph Medical

Center, in Burbank, the family has assumed leadership roles and donates

their time to numerous civic and charitable organizations. Today, the

Cusumano family is Burbank’s leader in philanthropic giving. Family

members have served on the board of directors of dozens of

organizations, including Woodbury University, the Burbank Chamber of

Commerce, and the Community Foundation of the Verdugos. In 2015, Chuck

Cusumano joined the Advisory Board of the Italian American Museum of Los

Angeles (IAMLA). During the late 1970's and the 1980's, Chuck hosted

the annual March of Dimes Western Fundraising Gala at his Toluca Lake

home. The Cusumano family is a principal benefactor of the

Providence St. Joseph Medical Center, having contributed to, among

other things, the Cusumano Family Neuroscience Center and the Cusumano

Family Radiation Oncology Department at the Providence St. Joseph Disney

Cancer Center.

|

|

|

|

|

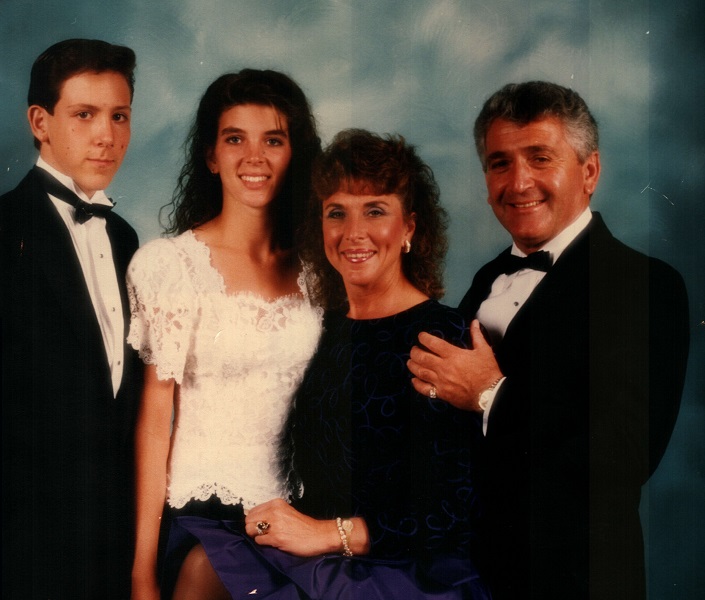

L-R: Bettina and

Charlie Cusumano, Evelyn and Roger Cusumano, Senator John McCain,

Caroline and Michael Cusumano, Irena Kovacs and Chuck Cusumano.

The family was the primary donor for the construction of a building to house the

Family Service Agency of Burbank, as well as the campaign to rebuild

Memorial Field at John Burroughs High School, where the main entry

court is dedicated to the family as “Cusumano Plaza.” In recent years,

the family has extended considerable support to wounded veterans

returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. The Boys and Girls Club of Burbank,

the American Cancer Society, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Boy and

Girl Scouts of America, Burbank Police Officers Association Foundation,

Chapman University, Goodwill Industries of Southern California, and

Habitat for Humanity are a few of the more than fifty organizations that

the Cusumano Family Foundation has supported.

|

|

|

|

Left: Julie Cusumano and her

children. Right: Sergeant Felice Cusumano, son of Charlie and Bettina

Cusumano, served in the United States Army’s 173rd Airborne in

Afghanistan.

Roger

and Evelyn are active in the Catholic Education Foundation, which

provides scholarships for underprivileged children to attend parochial

schools in Los Angeles County. After graduating from Loyola Marymount

University, Roger and Evelyn’s daughter Julie became an active member of

the Jesuit Volunteer Corps. She would later earn a master’s degree in

public administration from Portland State University. The couple’s son,

Anthony, is a devoted father of six children, and resides in Burbank.

|

|

|

Members of the Cusumano family gather for Christmas.

Family remains at the very center of operations at the Cusumano Group; their

unparalleled success is matched only by their ceaseless love for one another.

|

|

|

|

Top row (l-r): Caroline, Evelyn, and Bettina Cusumano. Bottom row, (l-r) Michael, Chuck,

Roger, and Charlie Cusumano.

|

|

|

|

The Italian American Museum of Los Angeles extends its warmest wishest for a bright holiday season.

Stay tuned for more exciting news in 2016!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|